In recent months, Turkey has experienced a seemingly renewed spate of terrorism, which has slightly declined over the year since spiking in the last decade, with attacks over the last ten years being claimed by Jihadists, Kurdish militants and leftist revolutionaries. In October of 2023, a Kurdish militant detonated a suicide bomb outside of the Turkish General Directorate of Security in Ankara, injuring two police officers. A second attacker failed to detonate his suicide bomb and was killed by police. The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) claimed responsibility for the attack. The government responded with some 20 airstrikes targeting PKK positions in northern Iraq and arrested dozens of people within Turkey.

At the end of January of this year, two masked gunmen stormed a Catholic church in Istanbul’s northeastern district of Sarıyer and fatally shot a Muslim man with disabilities who was attending Mass, hoping to receive charity after the service. The attack was claimed by the Islamic State (IS), and was answered by a string of arrests.

Then on February 6, two armed assailants got into a shootout with police at a security checkpoint outside of the Istanbul Palace of Justice—Turkey’s main courthouse, where many high-profile cases are tried, including terrorism cases. It is possible that there was an attempted attack inside the courthouse itself, according to one eye-witness, before the two militants outside got into a confrontation with police at the checkpoint, then drew pistols and started shooting. Another witness describes hearing between 20-25 shots fired. Two police officers and four civilians were wounded in the shootout before police shot the two attackers dead. One of the wounded civilians later died in the hospital.

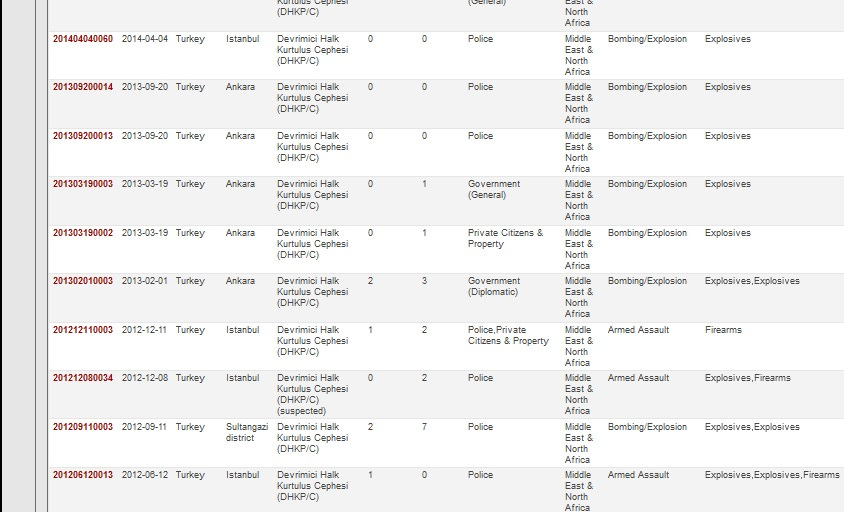

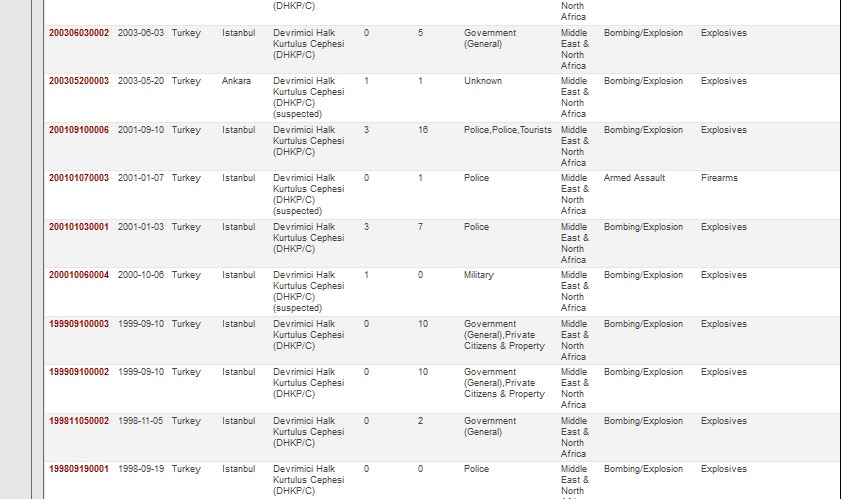

Turkish authorities attributed the attack to an obscure but surprisingly deadly Marxist-Leninist group, The Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C), officially established in 1994 but rooted in the student communist groups of the 1970s-1980s. Once again, Turkish authorities responded with a large series of raids and arrests, detaining 34 alleged DHKP/C affiliates.

DHKP/C is considered a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States and the European Union. The group seems to have a small presence outside of Turkey as well, particularly among the diaspora of Turkish nationals in Greece and Germany.

Despite Turkey’s multiple militant communist groups, DHKP/C stands out for both their brazen operational résumé over the last 30 years, as well as for taking some strong ideological and policy positions that have at times put them at odds with fellow Turkish Marxists and Kurdish Marxists both within Turkey and south of its borders.

The group's origins lie within the mass organization, the Revolutionary Youth Federation of Turkey (Dev-Genç), which was banned by the state in 1971 and split into multiple groups and sub-groups thereafter, one of which came to include Dev Sol, or Revolutionary Left, founded by a Kurdish Marxist, Dursun Karataş. Revolutionary Left had its own underground militant wing committed to insurgency against the Turkish state, known at its formation in 1978 as the Armed Fighting Units Against Fascist Terrorism (FTKSME). This was during a period of considerable civil conflict between the far-left and the far-right in Turkey, similar to Italy’s “Years of Lead” in the middle 20th century.

Over the next two decades, a complicated mixture of factionalism, power struggles and disagreements within the organization led Karataş and his supporters to form the party-cum-militia, DHKP/C, which was to legitimize itself through armed struggle just as Dev Sol had against not only the Turkish state, but perhaps just as importantly, against the right-wing government’s “imperialist” benefactors, NATO and the United States of America. Since its establishment in 1994, DHKP/C has maintained a fierce anti-NATO and anti-American position, and has carried out multiple attacks against US targets and interests in Turkey.

DHKP/C would also take with them Dev Sol’s banner of the red circle-star against a yellow background with hammer and sickle at its center.

An Abridged History of DHKP/C Attacks, 1996-2024

1996: January 9, DHKP/C assassins infiltrated the highly guarded Sabancı Towers and gunned down well-known Turkish businessman, Özdemir Sabancı, along with the General Manager of Toyota South Africa Motors and a secretary who was likely in the wrong place at the wrong time. The assassins were given access to the Sabancı building by a female employee who also happened to be a member of DHKP/C. Sabancı’s murder was highly significant not only due to his status within Turkey as a popular magnate and the fame of his family name, but it also became part of a greater saga in which a secretive group called “Ergenekon” was eventually exposed, leading to a high profile investigation and court case. The group was said to be comprised of members of the military and the intelligence services, and it is alleged that they had infiltrated and even fabricated multiple terrorist organizations in Turkey, who they are said to have used in order to create chaos, ethno-religious and political tensions, and general civil strife through bombings and assassinations of high profile figures, with the ultimate aim of toppling the ruling government and assuming power as a sort of junta. DHKP/C was accused of being one such construct, which they denied in a press release on their now-defunct website, entitled “The Old Theories About the Sabancı Center have Gone Mouldy!”

Despite being wanted on an INTERPOL Red Notice for terrorist activities in both Turkey and Belgium, the female DHKP/C member involved in the assassination has been on the run since the murders and her whereabouts remain unknown.

1997-1998: A series of bombings in which three people were collectively injured was attributed DHKP/C during this time.

1999: On September 10, two separate bombings targeting the Treasury building and the Labour and Social Security Ministry in Istanbul were attributed to DHKP/C. In each bombing, 10 people were reportedly injured. Seven suspected members of the group were later arrested following the night of bombings.

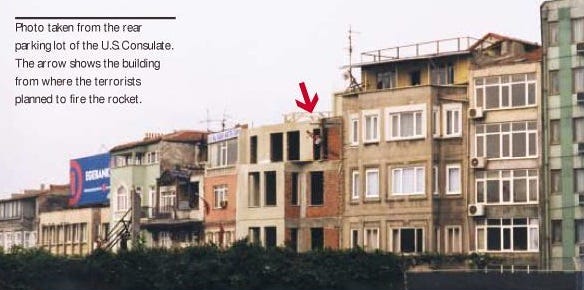

1999: Around 6:30AM, Turkish police stopped two men attempting to enter a construction site meters away from the US Consul General in Istanbul. The two men were quickly killed in an ensuing shootout with police, and a light anti-tank weapon (LAW) was discovered on them, which authorities believe they intended to use to fire a rocket at the US Consulate, which their predecessors, Dev Sol, had successfully done in 1992 on two separate occasions, neither of which caused any injuries. In a statement released following the 1999 attempt, DHKP/C said the failed attack was to be in retaliation for NATO’s air campaign against Yugoslavia, with whom they expressed solidarity. 1

2001: For the first time in their operational career as both Dev Sol and DHKP/C, the latter successfully adopted the new tactic of suicide bombings, which it would continue to employ well into the 2010s and will likely use again in the mid-2020s, should the organization survive. (There was an attempted suicide bombing targeting a military guest house in 1997, but it failed and led to the attacker’s arrest.) On January 3, DHKP/C member Gültekin Koç detonated a suicide bomb outside of a police station, killing three (plus himself) and injuring seven.

Four days after the bombing, two gunmen attacked a police patrol vehicle, injuring one officer before escaping on foot. Authorities blamed DHKP/C for the attack. Then, on September 10, a female suicide bomber blew up a police station in Taksim, Istanbul, killing herself, two police officers, and injuring an addition 16 officers and civilians.

2003-2005: On May 20, a female suicide bomber prematurely detonated a device in the bathroom of a cafe where she had been preparing to carry out an action against an unknown target. The blast killed her and injured one other person. A few weeks later, a DHKP/C operative detonated a remote controlled bomb next to a bus full of Turkish security court prosecutors and police, injuring five. Two other would-be DHKP/C suicide bombers were killed in separate incidents due to premature detonations in 2004 and 2005.

2008: DHKP/C’s Istanbul regional commander, Asuman Akça, was arrested for allegedly forming a plot to assassinate Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, but she was released after trial and subsequently murdered by a gunshot to the head. The alleged affiliations of her assassin again brought to the surface questions of an Ergenekon connection, and the shooter was accused of being a PKK member, separately a DHKP/C member seeking to prevent Akça from leaking to the media any supposed Ergenekon connections to the organization, and was even said to have possible ties to the underground communist Hoxhaist movement, MLKP.

2009: A female DHKP/C fighter was wounded, and she and her male comrade apprehended after attempting to kill former Justice Minister Hikmet Sami Türk in a bombing at a university as he gave a lecture on constitutional law.

2012: Two armed assaults led to the loss of four lives and the injury of another person, and on September 11, a DHKP/C militant entered a police station in the Sultangazi district of Istanbul, hurled a grenade at on-duty officers, which failed to explode, then detonated a suicide vest, killing one officer and injuring seven other people.

2013: On February 1, a man approached the security checkpoint of the US Embassy on John F Kennedy Avenue in Ankara, Turkey, made his way to the rear gates and detonated a suicide bomb, causing extensive damage to the checkpoint, killing two US-hired local security guards, and injuring three others. The bomber had been imprisoned previously for his 1997 bombing attempt on an army guesthouse. Perhaps a motivation for the bombing, by February of 2013, 85 suspected members of DHKP/C had been arrested by Turkish authorities since January of that year. Following the attack, the US State Department offered a reward of $3 million USD for information leading to the arrests of top DHKP/C leadership, and the CIA began working closely with their Turkish counterparts at the Turkish National Intelligence Agency (MİT) to monitor, track and dismantle the group.

At least three more attacks were carried out in 2013, one involving rockets fired at the General Directorate of Security. By September of 2013, DHKP/C street cadres and their supporters began having deadly clashes with local drug dealers in the Maltepe district of Istanbul. DHKP/C remains ideologically opposed to the sales of narcotics in its dwindling areas of influence.

2015: In January a female suicide bomber and member of DHKP/C blew herself up at a tourist police station in the Sultanahmet district of Istanbul, killing one police officer and wounding another. DHKP/C spokespersons said the attack was in retaliation for the police killing of a 15-year-old Kurdish boy, Berkin Elvin, who was fatally struck in the head by a tear gas round in the midst of 2013’s tumultuous Gezi Park protests and riots.

In March of that same year, DHKP/C militants disguised as lawyers entered the Palace of Justice in Istanbul and took prosecutor Mehmet Selim Kiraz hostage in his sixth-floor office. Police negotiated with the hostage-takers for six hours, who demanded authorities release the names of four individuals supposedly complicit in the death of Berkin Elvin, before shots were heard from inside the building and special police units stormed the courthouse, killing the assailants and finding the prosecutor critically injured, who later died from his gunshot wound(s). Before shooting the prosecutor, the hostage-takers posted grim photos of Kiraz, bound, gagged and a pistol to his head, with DHKP/C flags and a poster on the office wall behind them.

Then, on August 10, a string of attacks around 1:00AM rocked Instanbul and nearby Sirnak. DHKP/C insurgents detonated a VBIED outside of a police station injuring 10, followed by an armed assault on security forces six hours later, followed by a roadside bomb in Sirnak that killed four police officers and injured another, and finally an armed attack on a grounded military helicopter that killed one member of the gendarme. Finally, on the same morning, female militants shot up the US Embassy in Ankara with rifles. Two DHKP/C militants were killed in the series of attacks.

2016-2019: More attacks carried out in Turkey, employing both firearms and explosives, were mostly non-lethal but collectively claimed another half-dozen lives. The group began to become relatively quiet at the end of the 2010s.

2024: On February 6, two DHKP/C militants were shot dead at a security checkpoint outside of the Palace of Justice after attempting to carry out an attack on the courthouse. A civilian was killed, two others wounded and two police officers were wounded during the shootout between authorities and the armed militants.

Gallery of the Red Streets

DHKP/C Abroad

Greece

Like multiple other Turkish militant organizations, especially on the left, DHKP/C has had a relatively long and important relationship with neighboring Greece, both as something of a safe haven when fleeing Turkish authorities, as well as part of an organic network that includes Greece’s own extensive militant left-wing scene. In addition to seeking to build international networks of far-leftists, especially with those in close proximity to Turkey, Turkish revolutionaries have commonly sought escape to Greece, particularly following a high profile attack in Turkey and/or during waves of arrests, and they come both clandestinely as well as asylum-seekers. Finally, there seems to be some evidence of resource-sharing between Greek and Turkish militants, possibly including illegal weapons transfers.

In 2014, following a lead, the Greek National Intelligence Service (EYP), in coordination with the CIA and MİT, conducted a counter-terrorism operation in the Gizi neighborhood of Athens which netted several high-level DHKP/C militants, including one of the group’s leaders, Hüseyin Fevzi Tekin—who succeeded Dursun Karataş—and İsmail Akkol, who was wanted for his alleged involvement in the 1996 assassination of Özdemir Sabancı. Another of those arrested in the raids was Murat Korkut, accused of participating in a LAW rocket attack on the Ministry of Justice the prior year.

Nine of those arrested in later 2017 raids were accused of having drawn up plans to assassinate President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan during a state visit to Greece, in which they plotted to attack his motorcade from two sides using rocket launchers, hand grenades and Molotov cocktails.

Before the 2014 raid, Greek security forces had arrested another group of DHKP/C militants near the Turkish border who were suspected of planning an attack on Turkish soil.

In 2018, accused DHKP/C militant, Turgut Kaya, was arrested while trying to enter Greece and deported back to Turkey.

Perhaps one of the most noteworthy raids of all targeting DHKP/C members in Greece came in March 2020. During a raid carried out by Greek counter-terrorism units in the Athens neighborhoods of Sepolia and Exarcheia, police detained 26 suspected members of DHKP/C, many of whom were described as ethnic Kurds, and uncovered a massive cache of weapons that included an RPG-7 launcher, a Yugoslav M80 Zolja rocket launcher, multiple firearms, ammunition, and an underground tunnel network spanning some 40 meters beneath the dense neighborhood’s apartment blocks. 11 of those arrested were charged and are still incarcerated while awaiting the conclusion of their trials. In October of the same year, Turkey claimed to have arrested multiple high-ranking terrorists from different left-wing groups near the border with Greece in Edirne, including DHKP/C affliates and a member of the Liberation Army of the Workers and Peasants of Turkey, or TiKKO.

The location of the DHKP/C safehouse in Exarcheia is particularly significant, as it has long been known as a haven for militant anti-authoritarians who regularly clash with the Hellenic Police. Most of these groups are today comprised of dedicated anarchist street militants, and until recent crackdowns and raids, Exarcheia has been host to a vibrant universe of free, squatted buildings which might serve as Molotov cocktail factories, and/or legimitate spaces for political education, organization, art, performance, community networking, robust charity and mutual aid efforts.

As far as collaboration with Greek leftists and perhaps contemporary Greek anarchists, Turkish media reports that in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Turkish militant leftists were cooperating on arms acquisitions and the safe movement of fighters between the two countries as early as 1989, and that infamous Greek Marxist-Leninist terrorist organization, 17 November (17N), might have been a key player in these efforts. One specific report alleges that 17N transferred arms to Turkish counterparts within the Marxist-Leninist Armed Propaganda Union, or Turkey’s “Red Brigades,” and perhaps vice versa, until the latter was dismantled by Turkish authorities.

Germany

According to Germany’s Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, DHKP/C has had a significant presence amongst the sizable Turkish diaspora in that country since at least 1998. The bureau considers the DHKP/C to be the most serious of all Turkish leftist groups with a presence in Germany, and banned the organization in 1998.

DHKP-C uses cover names to conduct its politico-propagandist activities in our country. For instance, it operates under the name of People’s Front (Halk Cephesi) or under the name of its youth organisation Devrimci Gençlik (Dev Genç). Several local DHKP-C associations also use the name of People’s Council (Halk Meclis).

Militant actions and attacks carried out by DHKP-C in Turkey meet with a great response among its followers in Germany, and the organisation considers them an important means to strengthen cohesion and motivation. While DHKP-C sees Germany as a “safe haven”, the events it organises to commemorate its “martyrs” show that its Germany-based adherents, too, support the party line, including the terrorist option. The emphasis placed on the “revolution martyrs” as role models indicates that DHKP-C regards Germany and Europe as a base for the recruitment of new cadres and potential attackers.

German authorities further contend that DHKP/C has broad fundraising efforts across Europe, and that one such seemingly benign instrument of their fundraising is the left-wing folk music band, Grup Yorum, who organizes concerts and events across the European continent. Members of Grup Yorum have themselves been no strangers to political persecution from the Turkish state, and some have recently died while on hunger strike in Turkish prisons.

Hunger strikes and protests within detention facilities are not novel to DHKP/C and their affiliates, and in fact, during the group’s early days, some 60 members died in a combination of hunger strikes and violent crackdowns on prison protests, with the organization, like many left-wing militant groups, seeing prison as a sort of final front in their revolutionary struggle.

Additional EU Countries

DHKP/C is thought to possibly have a small presence in other EU countries such as Italy and Spain, perhaps France as well. Outside of the EU, other European countries are likely to host members and/or supporters, and at least one sympathetic website even offers news items and bulletins in Russian among other languages such as German and English.

Syria

Members of DHKP/C leadership initially supported the Kurdish breakaway region of Rojava in northern Syria during that country’s civil war up through the pivotal battle of Kobani, which pitted largely Marxist Kurdish forces against rapidly advancing IS Jihadist forces. However, as the war drug on, most within DHKP/C came to see the Kurdish militias in Syria as proxies of the United States and NATO, a country and a grand alliance that they see as “imperialist” powers, which they further feel have kept Turkey subjugated to the west. They thus came to support the Ba’athist government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and his allies, and some even joined the pro-Assad communist militia known by its Arabic name, “al-Muqāwamat al-Sūriyah,” or Syrian Resistance, which is largely considered a military offshoot of and ally to DHKP/C and fought alongside regular and irregular units of the Syrian Arab Army against IS and other foes.

DHKP/C’s Strength and Capabilities in 2024

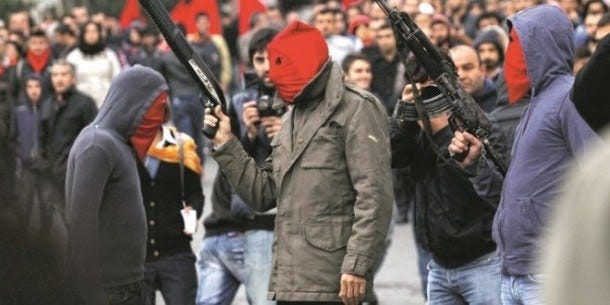

One of Militant Wire’s analysts with incredible knowledge of the militant far-left in Turkey estimates that the fighting manpower of the DHKP/C within Turkey might number as few as 100 committed militants. However, their ability to craft sophisticated explosives and carry out devastating attacks, as well as their continued access to small arms ranging from handguns—which are highly regulated in Turkey—to shotguns to Kalashnikov-pattern rifles is considerable. Furthermore, their cadres have displayed a deep ideological dedication to their cause and have demonstrated exceptional willingness to carry out incredibly risky, high-level operations within Turkey and without. Whatever lasting support they have among the diaspora should also be taken into account when assessing their enduring capabilities and support, though it should be noted that they compete with stronger and better organized Marxist organizations from the region with prominent presence among Turks and Kurds living abroad. Though dwindling since their formation, we have certainly not heard the last of DHKP/C’s operational cells and individual members.

United States Department of State: Bureau of Diplomatic Security, Political Violence against Americans 1999, (Washington, D.C.: 2000) 22.

Great article, thanks!