On 7th May, Afghanistan’s Taliban government, known as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA), announced new laws regarding women’s dress outside the home. Unlike the Taliban regime of the 1990s - and contrary to the reports of several international media outlets - the burqa (known in Afghanistan as chadari) has not been mandated, but women are advised not to step out of their house without covering everything but their eyes, particularly when speaking to men from outside their families. This move has sparked much social media debate over whether Islam actually prescribes such attire at all, and whether it is religiously required for a woman to cover her face. There has also been debate over whether such dress is even traditional in Afghanistan, as opposed to a recent Arabian importation. Some have pointed to the infamous photographs of students of Kabul University in the 1960s, in which bare-headed female undergraduates wear miniskirts, suggesting that Afghanistan was once, for a brief moment, on the brink of embracing Western ladies’ fashion.

In the southern Malay borderlands of Thailand a similar debate, albeit more muted in tone, has been underway for at least the past decade. The four southernmost provinces of Thailand – Songkhla, Pattani, Narathiwat and Yala – once formed the Sultanate of Patani Darussalaam, until successive attempts by its Siamese neighbours to the north finally subjugated the Sultanate to Bangkok rule in 1786, before subsuming it entirely into its borders in 1909 with the signing of the Anglo-Siamese Treaty. In the 1940s, resistance to Bangkok's rule began to emerge, until in the 1960s two armed liberation groups were established: the Patani United Liberation Organisation (PULO) and Barisan Revolusi Nasional (National Revolutionary Front, or BRN). At the core of these groups’ ideology has been a determination to assert Patani Malay Muslim identity, in contrast to the Thai Buddhist identity of what they see as their coloniser. From the 1970s, low-level violence perpetrated mainly by PULO gradually fizzled out towards the late-1980s. In 2004, BRN’s armed campaign burst onto the scene, kicked off by an arms raid on a military camp in Narathiwat province, ambushes on Thai troops and civilians (particularly teachers), bombings of bars selling alcohol, and beheadings of Buddhist monks. In the eighteen years since then, over 7,000 people have lost their lives (many fewer than Afghanistan, but already double the number of lives lost during 30 years of conflict in the north of Ireland).

The aggressive campaign initially took the Thai government by surprise, and questions immediately arose as to where the insurgent force had emerged from. It gradually became clear that BRN’s secret lay in a network of pondok schools – madrassahs – located throughout the four southern border provinces. It is now evident that most of BRN’s leadership is composed of ustaz (teachers of Islam). The former leader of BRN, Shafi’i (often mistransliterated Sapae-ing) Basor was the headmaster of Thammavitya School in Yala city; he fled to Malaysia just after the latest phase of the insurgency began, and died in Terangganu in 2017. His successor, Abdullah Wan Mat Noor, was the babo, or mullah, of Pondok Jihad school in Pattani province. Like Ustaz Shafi’i, Babo Abdullah went on the run in 2004. The leader of BRN’s political wing, Anas Abdurrahman (otherwise known as Ustaz Hipni Mareh) was a teacher at Thammavitya School. BRN’s foot soldiers are overwhelmingly sourced among madrassah students, or as they would be known in Afghanistan: Taliban.

Alongside the armed campaign, a religio-cultural struggle has also been fought, with an explicit Islamist agenda. BRN distills its own ideology into the first three letters of the Arabic alphabet: alif, ba, ta representing the Malay terms Agama, Bangsa, Tanahair: Religion, Ethnicity, Homeland. The struggle to liberate Patani from Thailand is couched in religious terms; an existential war to defend Islam against infidel Buddhist overlords, in which Patani Malays are compelled to participate on the Islamic basis of fardhu ‘ain (individual religious obligation). As such, emphasis is placed - in the pondoks; through sermons in mosques; and even through online propaganda – on the importance of observing proper Islamic dress and customs. Such guidance might easily be framed in terms of amr bil-maroof wa nahi an al-mankar: “prevention of vice and propagation of virtue”. Just as the IEA seeks to assert an identity based on Afghaniyyat and Islamiyyat - in direct contrast to the liberalizing agenda of the twenty-year Western intervention in Afghanistan - so BRN seeks to assert a Malay Muslim identity in contrast to the more liberal, Buddhist, Thais. Both the IEA and BRN have framed their armed struggles as anti-colonial (and not transnational) Jihad, and fighters who die for the cause of Patani freedom are commemorated as Shaheed – “martyr”.

As the Afghan Pashtuns remain cut off from their southern brethren by the Durand Line, a frontier drawn on a 19th Century map to divide Afghanistan from British India, so the Patani Malays remain cut off from their southern brethren by a century-old border designed to separate Siam from British Malaya. Whilst the IEA follows the Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence common throughout South Asia, BRN follows that of the majority of Muslims in Southeast Asia: the Shafi’i. Both the IEA and BRN have an antagonistic relationship with Salafists. Like the IEA, BRN’s religious practices demonstrate Sufi tendencies, and customs – such as the wearing of amulets - which Salafists would consider bid’a: forbidden “innovations”. Both the IEA and BRN represent versions of a very localised, traditional, Islam.

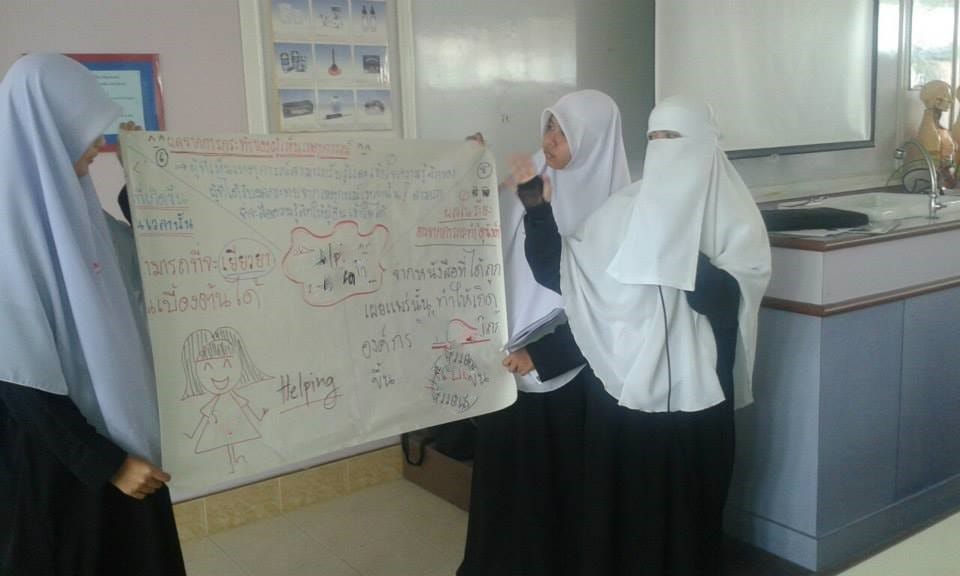

A century ago, few if any Malay women wore so much as a headscarf, but over the past twenty years even the niqab face veil has become increasingly popular, including amongst BRN’s grassroots supporters; it has become normal for many wives of BRN fighters captured by the Thai security forces to wear the niqab for the duration of their husbands’ absence from the home. It would be easy to see this as symptomatic of creeping Arabisation of Malay culture – as many have claimed the IEA’s latest edict is to Afghan culture. However, BRN’s grassroots are patriotically Malay nationalist, and the wearing of the long, Arab men’s thowb is discouraged, in favour of the baju melayu, sarong and songkok. Similarly, the IEA promotes for men a distinctly Afghan image of pirahan-tumban, waistcoat and turban. It is not Arabisation that is promoted, but Islamisation. Much as the IEA now sees its duty to guide the Afghan nation toward a more traditional and Islamic way of life, so BRN places importance on the continuing Islamic education of the Patani Malays, and the change in women’s dress over the past century is presented as a gradual trajectory towards a more Islamically-educated society.

The IEA’s peace process with the USA, culminating in the takeover of the country last August, turned heads in Patani. As BRN now engages in its own peace process with the Thai government (a Ramadan ceasefire recently came to an end) only time will tell how the conflict will be resolved. As in Afghanistan, however, the Islamisation of Patani society is set to continue.