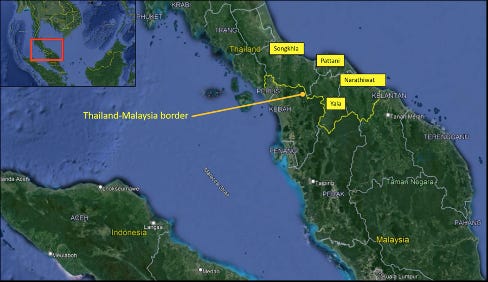

The insurgency in Thailand’s ‘Deep South’ has been ongoing for decades. Insurgents from the minority Malay-Muslim community have demanded autonomy from Buddhist-majority Thailand. As per the constitution, Thailand is “indivisible”. The Deep South covers the provinces of Pattani, Yala, Narathiwat, and parts of Songkhla. They were previously parts of the Sultanate of Patani (circa the 1450s - 1902, which encompassed the Deep South and parts of Malaysia). The Malay-Muslim population in the Deep South is culturally and historically closer to the Malays across the border. The conflict is motivated by this history. Thailand has generally taken a heavy security-based approach in the Deep South. There have been human rights violations by both sides. Recently, a pro-Islamic State East Asia (ISEA) channel released a claim of an attack in Pattani on April 15.

Trend of Violence

The trend of violence has ebbed and flowed over the years and, according to the Deep South Watch, between January 2004 and October 2021, at least 7,294 people have been killed and 13,550 have been injured. The latest peace talks, from 2019/2020, involve Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) and Bangkok. However, violence has continued despite the talks. A Ramadan ceasefire between the government and BRN was put in place.

Actors and Threats

There are several violent actors in Thailand’s Deep South, but BRN is the most operationally capable group. BRN used to conduct attacks when the Thai government was negotiating with Mara Patani, an umbrella network of separatist groups. Talks with Mara Patani were criticized because the active BRN faction was not in them, even though it was responsible for most violence. Attacks are used to gain leverage. BRN and other groups tend to have linked organizations, offshoots, or splinters. The Runda Kumpulan Kecil (RKK) is considered to be an especially violent offshoot of BRN. There are several more groups in this murky environment as insurgent cells are small, localized, and often linked by family, clan, or other relations. Due to the decentralization, senior members of outfits cannot always control these cells, which sometimes act opportunistically. A lot of attacks go unclaimed, and Bangkok’s narrative on incidents is often disputed.

Security forces are the most targeted. There have been attacks on Buddhist monks, civilians, and government figures (election periods see heightened risk). Infrastructure (including security) is also targeted with the aim of disrupting the Thai government’s ability to govern. There are also firefights with government forces. Insurgents carry out bomb attacks (the use of IEDs is widespread, double-taps are fairly common too), targeted killings, ambushes, and others. BRN can conduct coordinated attacks across the Deep South. Deep South insurgents are suspected to be behind some attacks in Bangkok. There have been coordinated campaigns in the past in the Deep South. Groups generally have a degree of public support. Thailand has a large number of small arms (relative to the Asia Pacific in general), as well. Weapons also cross the borders of Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, and Malaysia. The wider region has been wracked with conflict, especially in the post-WWII era. Small arms proliferation is extensive. The Thai government has in the past given weapons to local defense volunteers helping with counterinsurgency in the Deep South. Insurgents also capture weapons from Thai security forces. Military issue M16s and AK variants are common in the hands of separatists.

The Patani United Liberation Organisation (PULO) claimed the April 15 Pattani bombing, which killed one civilian and injured three bomb unit personnel (the attack is the one claimed by the pro-IS channel). G5, under PULO, conducted the attack. PULO said the Thai government should negotiate with all groups in the Deep South, adding that the BRN did not solely represent Patani (referring to the Sultanate of Patani). Its president Kasturi Mahkota said that the attack “represents business as usual for PULO.” Kasturi represented PULO in the peace talks between the government and Mara Patani. PULO’s last claimed attack was in 2016, so their capabilities are in question.

Legal trade between Malaysia and Thailand through this border is valued at 19 billion USD. Parts of the border with Malaysia are fairly porous, especially in the mountains and jungle. Criminal networks (involved in trafficking, smuggling, et al), refugees, and undocumented migrants all flow across the border. Insurgents move back and forth across the border as well; they even have some local support on the Malaysian side.

Connections to Regional and Transnational Groups

There are several connections between Thai insurgents and regional and transnational groups. Some members of a new iteration of PULO (formed in 1995) trained in Libya and Syria. Some RKK insurgents have had training in Indonesia in the 1990s and 2000s. The Gerakan Mujahideen Islami Pattani (GMIP) had links to the Philippines-based Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Indonesia-based Free Aceh Movement (GAM). GMIP and BRN had members trained in Afghanistan, and some in the former voiced support for Osama bin Laden. Indonesia’s Jemaah Islamiyah reached out to GMIP. Some BRN members apparently trained in Indonesia. The strength of these connections is unclear. Some are not believed to be there anymore. Many of the organizations have changed considerably since the 1990s and 2000s when most of the links were active. And despite these connections, attempts to bring the Deep South conflict under global jihad have not succeeded.

The Islamic State

Global terror groups have largely ignored this conflict. There are elements amongst the separatists who are more hardline or have been exposed to more extremist ideologies. There have been unverified claims of Thai militants pledging allegiance to the Islamic State (IS). Pro-IS propagandists are trying to bring Thai separatists under the banner of global jihad and the IS ideology worldview. They have been unsuccessful thus far. It seems they are ‘testing the waters’ with respect to pro-IS media activity in Thailand. (Some of the recent claims are detailed here).

Islamic State East Asia and IS-linked or affiliated groups in Southeast Asia have gotten weaker operationally. Security forces in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Malaysia have been cracking down hard on terror groups. IS, for instance, lost Marawi (its failed attempt at establishing a caliphate in Southeast Asia; IS had helped with funding, online messaging, techniques to fight in urban terrains, telling trained foreign fighters to join, etc.). Outfits like the Philippines-based Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters and Abu Sayyaf Group, and Indonesia’s Jamaah Ansharut Daulah, are on the back foot. Being able to claim attacks in Thailand would help ISEA’s brand. Ramadan may have provided another motivation for the April 15 claim. Pro-IS messaging regarding Thailand could increase more this year.

It is unlikely that an IS-linked group will be able to establish a presence and be operationally capable in the Deep South in the current conditions. The extremist or IS-level-radicalized subset of the Thai insurgents is very small. There have been killings of Buddhist monks for instance, and religious aspects to the conflict. However, it is more separatist and (larger)-identity-based in nature. PULO conducted the April 15 attack because it was left out of peace talks and not for IS or its ideology. Similarly, insurgents, and not IS-linked militant groups (whose presence is still unproven in Thailand), are suspected of conducting the January 3 Narathiwat attack (that pro-IS channels claimed).

Some in PULO or other groups could possibly be more ambivalent to IS, but overall groups will not be. Support for IS groups from long-standing established insurgent groups is far-fetched. Younger and more disenchanted insurgents could possibly be vulnerable to their propaganda. But family ties, village heads, and elders maintain a strong community presence and could offset such attempts. The hardline elements amongst the separatists who would be sympathetic to the IS are exceptions and not the norm. The wider public will not give IS-linked groups a warm welcome. IS-linked groups will have trouble garnering local support, which will also affect their ability to operate and organize logistics.

If an IS-linked group does emerge in Thailand, Bangkok would likely take an extremely harsh security force response to deal with the terrorists. “Terrorism” in the country could impact image, investment, and the tourist economy, and raise questions about the administration and military’s ability to maintain security. There will be opposition to IS-linked groups, not only from the local public but from separatist groups too, who will attack them. IS-linked groups will attract bad press and delegitimize the insurgents’ position. They have more incentives to block the formation of IS-linked groups than they have to be affiliated with IS.

Current Status of the Deep South

The nature of the Deep South conflict is not going to change anytime soon. In time, there could be some groups in line with IS or similar ideologies, but for that, the current conditions will have to change. G5 left a message during the April 15 attack, which said “Long Live the King; G5 Patani Royal Army.” The idea of the Sultanate of Patani is stronger than that of a global caliphate. Pro-IS groups will continue their propaganda targeting Thailand though and try to get more local support. The violence in the Deep South is going to continue regardless, as a political resolution is still difficult to see for the foreseeable future.