There is a little-known militant group currently operating in Nigeria which has been around since about 2016-2017. They are known as the Lakurawa, which officials in Abuja are taking quite seriously and trying to stamp out before the group has an opportunity to form lasting roots, as have other insurgencies in the country. Their name is derived from the French phrase “La Recru” meaning “the recruit”. They are known to operate in both the Nigerian states of Sokoto and Kebbi. They were first identified in 2018, and according to more recent reporting they have since expanded their reach into Niger State and Kaduna. There is additional evidence that suggests the group was founded to fill a void left by Nigerian state agencies to protect from armed bandits operating out of Zamfara State.

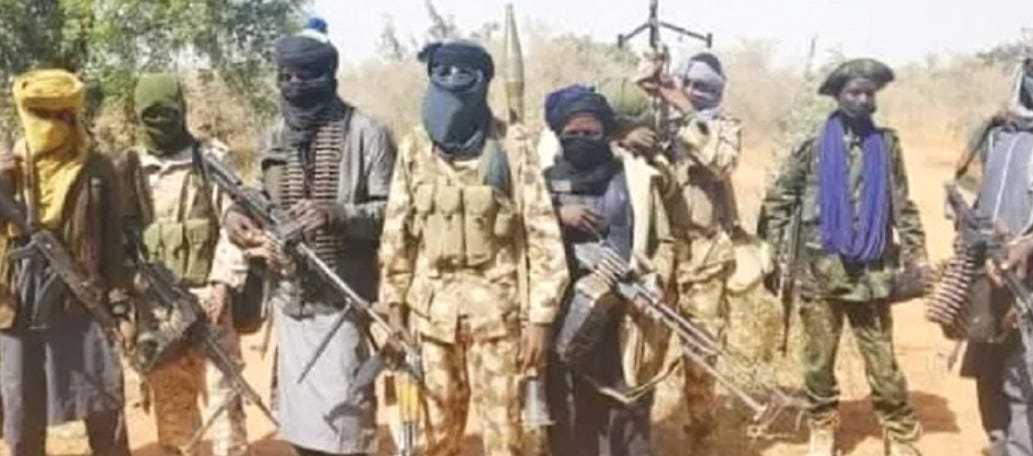

The question regarding the sudden impact of the group upon Nigerian state security is worthy of both discussion and investigation. It appears that the military and media outlets have agreed on a similar message: “The Lakurawa are affiliated with terrorists organizations operating in the Sahel, particularly from Mali and Niger Republic.” The threat has been defined by these state instututions as being external rather than being an internal situation of which the current leadership in Nigeria has lost control. Another assessment finds that the group has had success “exploiting weak intelligence frameworks, porous borders, and socio-economic vulnerabilities to wreak havoc on communities in mainly parts of Kebbi and Sokoto State.”

In recent weeks the Nigerian military has claimed a victory over the group in Tangaza, part of the Augie Local Government Area (LGA) in Kebbi State. How did they define this victory? Were the Nigerian military able to prevent the group from capturing a population center? In either such context it may be practical to declare victory by military force, however, how the group reacts and where their next operation takes place may indicate if the strategy currently being employed against the them will ultimately prevail, or if they are simply playing whack-a-mole.

The operation at Tangaza relied heavily upon government airpower, highlighting a significant flaw within their general strategy. Often we hear of a Nigerian airstrike that killed dozens or hundreds of fighters belonging to either Boko Haram or the Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP). However, these strikes do not seem to deter or hinder the major operations of these groups, as they often launch reprisal raids and attacks. This fact alone begs the question of whether the Nigerian military has conducted proper Battle Damage Assessments (BDA) to accurately calculate the number of casualties that they have inflicted, particularly via air support.

When it comes to nations having serious domestic security issues, they often emanate from either one of two sources: poor governance within their own borders, or they are neighbors to a country that is suffering itself from an insurgency, a common feature of which being a certain porosity of borders, and even the exploitation of such conflicts by other hostile states to the advantage of armed groups. Nigeria currently finds itself in a precarious situation where both of these are contributing factors to its overall security landscape.

We have known for some time now that the Nigerian government has struggled against both Boko Haram and ISWAP. These militant organizations have spread into neighboring Cameroon and Chad. Add to this whole picture of destabilization the coups that have taken place in Mali, the Niger Republic and Burkina Faso, and this presents a complex of milieu of security challenges with which West African governments are currently faced.

So, how is there current leadership in Nigeria faring? The answer depends on who you are asking. The military is stating that it is responding to all threats, however we see banditry and more militancy spreading across the country, to include the growing influence of groups like the Lakurawa. The government has been slow to designate and respond to threats, perhaps due to issues of capability, leaving internal states in the lurch. It appears that this dynamic will not be resolved anytime soon.

At the very least, Nigeria will require leaders that are willing to work with their neighbors on their internal security to reduce the threats to itself and the region as a whole, as well as remain open to cooperating with neighboring states on their own security issues, all of which seem to affect and interact with one another.

Great read, but unfortunately I disagree that there is a consensus on who or what Lakurawa is connected to. Despite mounting evidence, Nigerian media and government officials still decide to paint the issue as a local one, rather than one connected to IS-Sahel Province. It’s been frustrating to watch. Otherwise, great analysis.