Bombing McDonalds: Why the Revolutionary Organization—17 November Attacked Three Big Symbols of U.S. Capitalism in 1998

At 3:50 AM on February 3rd, 1998, a bomb exploded outside of a McDonalds in the Chalandri borough of Athens, Greece, toppling tables and chairs and throwing glass across the empty restaurant. Approximately ten minutes later another bomb exploded outside of a second McDonalds location, one borough north in Vrilissia. “No one was hurt in either attack and the material damage was minimal.” Both bombs consisted of two sticks of dynamite, a clock and a battery—familiar trade-craft of Greece’s oldest extant domestic terrorist organization. The early morning McDonalds bombings were part of a series of attacks that would take place in Athens between February and April of that year. All would be claimed by the Revolutionary Organization—17 November (17N), then in the 23rd year of their operational career.

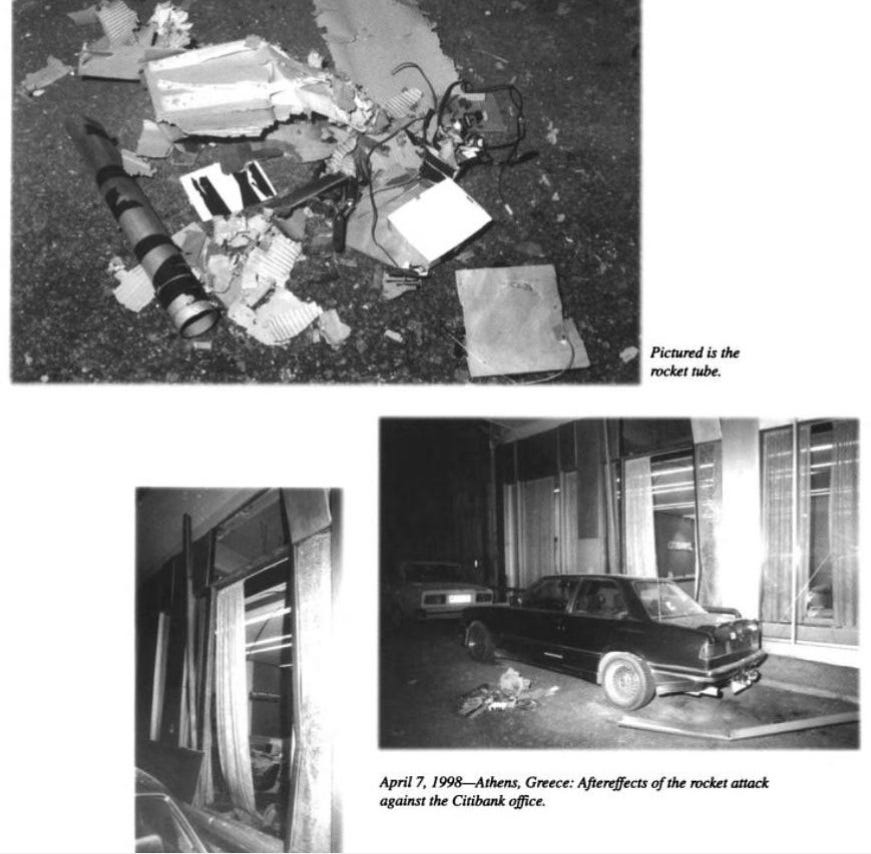

Two weeks after the McDonalds bombings, an improvised explosive device was detonated just after midnight outside the showroom of a General Motors dealership on Kifissias Avenue, also in northern Athens. On March 12th a bomb was detonated under a car in the lot of a Chrysler dealership in Athens, this time leading to significant damage but again no casualties. Five minutes later, a bomb that had been placed outside of the boiler room in the garage of an Opel dealership in Athens exploded, also causing extensive damage. (At the time Opel was owned by General Motors.) Finally, near midnight on April 7th, someone fired an anti-tank rocket into the offices of a Citibank location in Athens.

Just after the rocket attack on Citibank, 17N released an eight-page communique to Greek daily newspaper Eleftherotypia claiming all six attacks. According to the claim, the spate of bombings and the rocket were in retaliation for US and NATO foreign policy, particularly in the Aegean Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean. Two years earlier, Greece had nearly gone to war with neighbor and fellow NATO ally Turkey over a pair of uninhabited islets between Greece’s Dodecanese Island chain and the Turkish coast. Though the issue was resolved without any territorial losses to Greece, lingering tensions between the two countries coupled with a perceived history of American imperialism favoring the Turks in the region added to an anti-US sentiment that had long since existed in Greece and which endures today.

Flag Wars in the Aegean

In the winter of 1995-1996, a curious little maritime incident nearly brought Greece and Turkey to war with each other, nominally over a pair of uninhabited rocks (save for a herd of Greek sheep) jutting out of the Icarian Sea near the Turkish coastal city of Bodrum, which the Greeks call “Imia” and the Turks call “Kardak”. On December 26th Turkish cargo vessel “Figen Akat” ran aground on the easternmost point of the littlest Imia islet and radioed for help. The captain was contacted by the Kalolimnos Port Authority and notified that a Greek tugboat had been dispatched to assist. When the tug arrived, the Turkish captain insisted that he was aground in Turkish territory and that he would wait until Turkish vessels arrived to free him. The captain of the Greek tug, however, was intent on collecting the salvage fees from the Figen Akat after they had made it back to port. The captain of the Figen Akat eventually relented, and when the cargo vessel made it back to the nearest Turkish port with the assistance of the Greek tug, the latter’s captain filed the formal paperwork to claim his salvage fees, which was immediately disputed by the skipper of the Figen Akat, who maintained that he never left Turkish territory and was appropriately awaiting Turkish rescue.

What should have been a mundane dispute sorted out by bureaucrats instead escalated into a serious international incident, largely owing to the politically weak positions of both the Greek and Turkish governments domestically. Some initial diplomatic confusion, or at the least a misunderstanding, also seems to have played a role, though nationalists on either side were allowed to steer the conversation in their own countries and the situation spiraled into a genuine crisis after both sides claimed sovereignty over Imia/Kardak. Newly elected Greek Prime Minister, Kostas Simitis, was surrounded by a cabinet full of nationalists, and by early January 1996, the Greek press began pressuring him on the Imia/Kardak issue.

On January 25th, “Greeks who lived on the nearby island of Kalymnos sailed to Imia and raised the Greek flag there. Turkish media suddenly took notice, and a team of reporters from the newspaper Hürriyet were dispatched to the islets […] to unfurl their own country’s flag on live television.” The Greek and Turkish navy took to posturing around the islets as the prime ministers of both countries traded barbs. Turkish armored units moved towards the Green Line dividing Cyprus, and Greek Cypriot forces were put on high alert. On the 28th and 30th of January, special forces teams from both countries made separate landings on the islets to again raise the Greek and Turkish flag respectively, and then, predictably, tragedy struck. Around 5:30 AM on January 31st, a Greek helicopter took off from the deck of the Navarino on a reconnaissance mission and crashed, killing three Greek naval officers: Christodoulos Karathanasis, Panagiotis Vlahakos, and Ektoras Gialopsos. “Although the incident was covered up at the time, there are allegations the helicopter had been fired upon by Turkish forces.”

Talks between the two sides became impossible. In the end, it was the all-night phone line efforts of then-US Assistant Secretary of State, Richard Holbrooke, that managed to de-escalate the crisis and get both sides to return to the status quo ante. Though the crisis was resolved between the two nations, it proved politically damaging for the Simitis administration, whom fellow Greeks accused of treason.

The Imia crisis nearly brought the two countries into open military conflict with one another, but it was not the only or even the worst such incident since the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. Two decades prior to the Imia crisis, Greece and Turkey had gone to war for four weeks on the island of Cyprus, during which thousands were killed on both sides and thousands more ethnic Greek and Turkish Cypriot civilians were displaced. Turkey still occupies the northern 35% of the island today.

Tensions remain high between Greece and Turkey, especially in the Aegean and broader Eastern Mediterranean. But at the end of the 1990s, when the United States shared a much closer relationship with Turkey than it does today under the leadership of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, US and NATO foreign policy in the Eastern Mediterranean was the primary motivation for terrorist attacks perpetrated by Greece’s red urban guerrillas, who by the end of the decade had made Greece the most dangerous country in Europe for western diplomats and businessmen.

“The Greek Waterloo”

At 11:45 PM on the 7th of April 1998, someone parked a car on the street about six meters away from the outer windows of a Citibank office in Athens, Greece. After leaving the immediate area, the driver or an associate used a garage door opener to remotely fire an anti-tank rocket into the building from a makeshift launcher fixed atop of the car. The rocket penetrated the office but it did not explode, and no one was killed or injured in the attack. The Marxist-Leninist urban guerrilla group Revolutionary Organization—17 November would release a claim for the rocket attack and five previous bombings that year in an eight-page communique, which they sent to Greek newspaper Eleftherotypia.

The indignation expressed in the claim regarding both the Imia crisis itself as well as its conclusion is significant. The author(s) call the incident “the Greek Waterloo,” and begin the claim by addressing a resurgent anti-American sentiment in Greece, which perhaps peaked a year later with the NATO air campaign targeting Yugoslavia:

According to a poll conducted and published in a pro-government newspaper in January '97, a year after Imia, 68.9% of respondents were asked whether Greece should rely on US mediation to resolve the Greek-Turkish dispute. When asked if they have confidence in US mediation in resolving the Cyprus issue, 85% answered in the negative and only 13% have confidence in the US.

In another poll conducted in June 1997 and published in another pro-government newspaper, only 23.1% answered positively for the foreign policy of the Simitis government and 47% negatively. Finally, according to the first poll, the negative opinions about the USA do not come from a certain political space as before, but from all political spaces from the left to the right.

These numbers are impressive considering that they come from opinion polls, that the USA is an "ally and friend country," that Prime Minister Simitis publicly thanked them in Parliament for their role on the night of the crisis in Imia […]

[The polls] show unequivocally that the vast majority of the Greek people consider that the USA as the only sovereign superpower today is not only neutral but that it is primarily responsible for both the ongoing Turkish occupation of Cyprus and for all the provocative Turkish claims to of the sovereign rights of the country in the Aegean.

Over another seven pages, the claim goes on to accuse the US of seeking to divide the Aegean and positions Turkey as America’s “over-equipped” gendarme in the region. The author/s fault the US for forbidding Greece from purchasing weapons systems “from present-day capitalist Russia” so that Greece might approach military parity with Turkey and cite US intervention in the South Korean purchase of Russian S-300 air defense systems as an example of this policy in practice elsewhere. The claim further condemns both the Greek elite and bourgeoisie for effectively decamping from the country in terms of their greater loyalties in favor of a western hegemony with which they cannot compete, placing the fighters of groups like 17N as the country’s remaining patriots, whose nationalism they contrast with the “racism” of their right-wing nationalist countrymen.

So, we decided to strike at American imperialism-nationalism for what it is plotting against the sovereign rights of the country. For being the main one responsible for the perpetuation of the Turkish occupation in Cyprus, for the Turkish claims in the Aegean at the expense of the sovereign rights of the country, for the planned division of the Aegean and the placement of the over-equipped Turkish soldier as a gendarme [over half of the] Aegean. We are responsible for the bombings against two branches of the American chain of stores McDonalds, the American car dealership General Motors, Chrysler, Opel (a subsidiary of General Motors in Germany) and the rocket attack at Citibank.

- Revolutionary Organization 17 NOEMBPH, Athens April ‘98

Enduring anti-US/NATO Sentiment in Greece

One of the notable aspects of 17N’s winter/spring campaign of 1998 is that it was non-lethal, where so many of their attacks had claimed the lives of high-level western intelligence officers, diplomats, journalists and businessmen. On the very same avenue where they rather benignly blew up an SUV from Chrysler’s retail inventory, 17N would carry out their last successful operation which like many of their previous was both a high-profile and bloody affair: the assassination of British military attaché Brigadier Stephen Saunders in which two members of 17N on a motorcycle pulled up alongside Saunders on Kifissias Avenue while driving to the British embassy and shot him dead in morning traffic. That a group with such capability would take the time to bomb a franchise restaurant is somewhat remarkable, and surely speaks to the symbolic importance that 17N attached to McDonalds, in this case, as a symbol of capitalism and US imperialism. (Incidentally, 17N’s equally capable successor urban guerrilla group, Revolutionary Struggle, also dynamited an Athens McDonalds in 2009.)

As for the anti-American, and especially the anti-NATO sentiment that motivated 17N’s 1998 campaign, though it might have ebbed and flowed since 1998, it seems to again be on the rise. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has somewhat divided both the Greek right and left, but the parliamentary communist KKE party and its counterparts have maintained a firm stance against NATO and any further enlargement of the organization. Recently, members of KKE and the affiliated KNE threw red paint on a frigate of the Royal Canadian Navy docked in Greece’s Piraeus Port. In a similar scene, port workers and members of left-wing trade unions tried to halt a convoy of NATO military vehicles traveling through Greece to Ukraine, in which they spray painted anti-NATO slogans on some vehicles using red paint.

Today’s urban guerrillas in Greece are overwhelmingly anarchists, rather than Marxist-Leninists. And though they share many of the same critiques of NATO, the United States and of the West in general with those of their Marxist counterparts, the issues presently facing them are much different. Though there is no shortage of American fast-food franchises and other signs of US imperialism throughout the tourist-heavy areas of Greece, modern urban guerrillas would probably argue that there are US corporations today that are more insidious than McDonalds, such as AirBNB. As neighborhoods like Exarcheia in downtown Athens are increasingly gentrified to accommodate tourists at the expense of locals, for example, we can expect a more contemporary target-selection from today’s urban guerrillas in Greece, and the McDonalds may not be as vulnerable as, say, the Amazon delivery van.

NATO itself will remain in the cross-hairs of Greek insurgents. Greece’s latest anarchist urban guerilla outfit, the Direct Action Cells (DAC) detonated an improvised incendiary device fashioned from butane gas canisters outside of a Hellenic Army barracks adjacent to NATO facilities north of Thessaloniki in 2021. However, the nature of the device itself when compared to the IEDs employed by older groups such as 17N, as well the DAC’s history of similarly crude attacks suggests that they lack the capability to carry out the kind of sophisticated campaign of assassinations and bombings that was executed by 17N.