The development and use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV), commonly known as drones, is one of the defining features of conflict in the early 21st century. While the primary role of drones on the battlefield has been that of surveillance, they have also been used for the purposes of conducting strike operations, particularly by the US military and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) on the battlefields of the Global War on Terror (GWOT). While drones have been largely used by state actors, non-state actors have also used drones for multiple purposes. Notably, since 2014 groups like the Islamic State (IS) have used small, off-the-shelf drones for both reconnaissance and strike missions. Furthermore, drones have been used as parts of attacks against national political leaders. These attacks include both the 2018 attempted assassination of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, and the 2024 attempted assassination of Donald Trump. The war in Ukraine, which expanded in early 2022 to a full-blown state-on-state armed conflict, has brought about the use of small drones for the purposes of strike operations where previously they were almost exclusively conducted by much larger systems, which portends a rapidly arriving era of cheap and effective political assassinations.

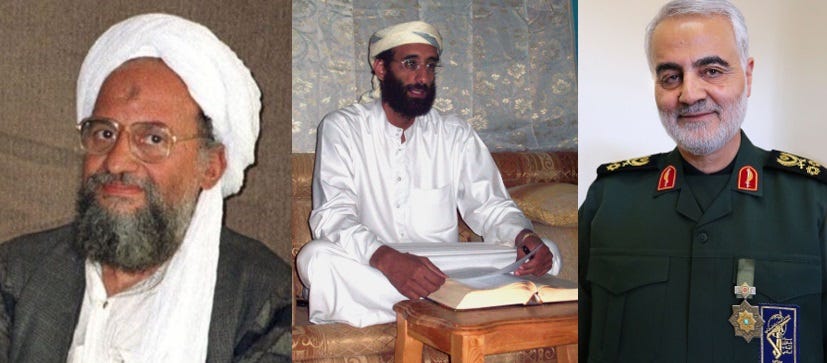

When discussing drone assassinations, many people think of the US security services’ use of large drones such as the Predator and Reaper fixed-wing drones on the battlefields of the GWOT. The Predator and Reaper are roughly the size of a light airplane and are often armed with Hellfire Missiles. The US government conducted a number of high-profile targeted killings, commonly referred to as assassinations, over the course of the 20-year GWOT. Some of these notable operations include the killings of: Ayman al-Zawahiri, al-Qaeda’s leader after the death of Osama bin Laden; Anwar al-Awlaki a US citizen jihadist propagandist; and Qasem Soleimani, an Iranian general, who the US held responsible for numerous attacks against Americans and American interests throughout the Middle East. Typically, the US government would employ drones in either personality or signature strikes.; the former targeting a specific individual based on their identity, with the latter targeting unknown persons based on their behavior and the belief that said behavior indicates that they are engaged in terrorist or combatant activities. (It is important to note that under Executive Order 12333, the US government prohibits assassinations.)

However, the definition of “assassination” is not given in the executive order and is therefore unclear. Yet, a working definition of something like: “an assassination may be viewed as an intentional killing of a targeted individual committed for political purposes…in peacetime” likely fits the bill. While some of the GWOT’s drone strikes were carried out by the CIA under Title 50 of the US Code, which provides the legal frameworks for the intelligence operations of the US government, the majority of them were conducted by the US military under Title 10 authority, which provides the justification (albeit ambiguous) for military operations of the US government. Importantly, all the individuals killed under the GWOT’s drone targeted killing program were killed for what amounts to military reasons. Even targets such as Anwar al-Awlaki and Qasem Soleimani were engaged in military or terrorist action against the United States government. While some people would argue that the targeted killings carried out by the US government during the GWOT were assassinations, especially killings carried out outside of a declared warzone, these killings still have a very different valence from the killings of, say, Alexander Litvinenko, a former KGB officer, who was killed by poisoning with Polonium-210, or Ngo Dinh Diem, the first President of South Vietnam who was executed following a CIA-backed coup. The US government’s program of targeted killings using drones has historically relied upon large drones that use weapons such as missiles and munitions to conduct strikes in the same manner as do conventional aircraft. However, these kinds of drones were out of reach of non-state actors, but the introduction of small commercial drones has empowered these less well-resourced entities to use drones as well.

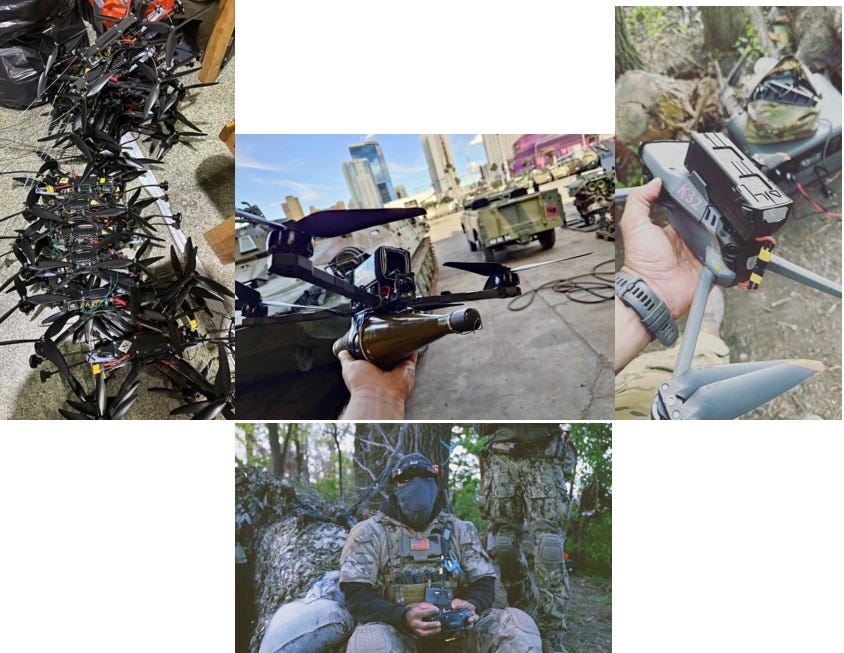

Widely available, cheap, and easy-to-fly commercial drones did not come to market until the 2013 release of the DJI Phantom. Once these drones were available, IS almost immediately used them. Initially, IS used drones to conduct reconnaissance and record attacks for propaganda purposes. However, by 2016 IS was also using drones to conduct strike missions. In the case of small drones (often “quad-copter” (rotary)) strikes are conducted either by dropping a munition such as a grenade or mortar round onto a target, or come in the form of a kamikaze attack where the drone is flown into or close to a target and detonated by proximity or impact (“FPV”, or first-person-view, drones). By 2016, but as early as 2015, IS was using drones for both of these types of strikes. The use of small drones by IS was such a problem that in 2017 the then-commander of US Joint Special Operations Command identified it as one of the greatest threats that his command was dealing with. That said, IS isn’t the only non-state actor in the Middle East that is using drones in conflict. Notably, Houthi rebels used Iran-supplied Qasef-2K loitering munitions to target Yemeni military leadership in 2019. This latter kind of attack was conducted in an effort to kill specific individuals. Though, the targeted individuals were members of the military and the strike occurred during a time of war, thereby making it more similar to the US government's targeted killing program than to a political assassination, which would be aimed at a civilian political figure during peacetime.

The most notable cases of attempted political assassinations in peacetime using drones happened in 2018 and 2024. The first was the attempted assassination of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. Maduro has been ruling Venezuela as an autocrat since 2013 when he replaced socialist strongman Hugo Chávez following the latter’s death from cancer. Maduro’s persecution of political opponents through actions such as jailing members of opposition parties, arming and backing radical leftwing paramilitary gangs known as colectivos that harass and murder opponents of socialism, and the use of government death squads known as Special Actions Forces (FAES), has earned Maduro many enemies in his own country. On August 4, 2018, some of Maduro’s opponents attempted to assassinate him via drones laden with explosives. Two DJI Matrice 600 drones with what Venezuelan authorities claim was C4 plastic explosive were flown toward Maduro as he made a speech in front of members of the Venezuelan National Guard. Neither of the drones made it close enough to harm Maduro, though seven members of the Venezuelan National Guard were injured. In this case, the drones were used for a strike in a kamikaze-style attack. The attack itself proved to be unsuccessful because the drones detonated prematurely before they had reached their target. It is unknown how their payload was detonated.

The second was the attempted assassination of former US President Donald Trump. In this case, a drone, only identified as from the manufacturer DJI, was used to scout the area where Trump would be speaking later in the day. The actual assassination attempt was conducted by a sniper, who miraculously missed the President.

Since the failed 2018 assassination attempt on Nicolás Maduro, small-strike drones have made dramatic technological progress, and they will pose a much larger danger to political figures around the globe, and it is not likely that future assassination attempts that use drones will only use them for surveillance.

Since the Winter of 2022 and the expansion of the war in Ukraine, small drones have been used increasingly for strike missions. The most notable innovation has been the use of FPV drones in kamikaze-style attacks. Working in concert with drone teams using DJI-style camera drones for surveillance, Ukrainian and Russian forces will fly FPV drones laden with rocket-propelled grenade warheads, mortar rounds, and improvised explosives into targets. These FPV drones were designed for activities such as drone racing, and are much faster and more agile than a standard DJI camera drone. The basic tactics for the use of drones in combat in Ukraine are similar to sniper teams that use spotters and shooters in concert to locate and attack targets. The technology to build FPV drones is widely available and affordable on the hobby market, and the amount of training and practice needed to become a skilled enough pilot needed to fly an FPV drone into a man-sized target is well within the reach of an average person.

The proliferation of affordable and easily piloted FPV drones, along with the larger numbers of skilled operators that the war in Ukraine is generating, likely heralds a future where FPV drones are used in attempted political assassinations with some degree of regularity. Already, assassination attempts are being conducted with the use of drones as in the cases of Nicolás Maduro and Donald Trump. So too are improvised weapons being used, as in the case of the successful assassination of Shinzo Abe. The greatest barrier to the use of drones for peacetime political assassinations will likely be the assassin’s ability to obtain and safely work with a suitable explosive payload for the drone to be used in the attack. With the technology and skilled operators widely available, the world awaits the first attempt for this new type of method to be used in a peacetime political assassination attempt. This is a danger that would increase substantially in the event that autonomous or semi-autonomous drones were to become ubiquitous.